Safe Read online

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © 2020 by James Siegel

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTON and the D colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Barnett, S. K., 1954– author.

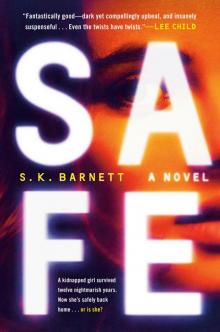

Title: Safe : a novel / S. K. Barnett.

Description: New York : Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, [2020] | Identifiers: LCCN 2019031321 (print) | LCCN 2019031322 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524746520 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781524746544 (ebook)

Subjects: GSAFD: Suspense fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3569.I3747 S24 2020 (print) | LCC PS3569.I3747 (ebook) | DDC 813/.54—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019031321

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019031322

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

pid_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

To Laura—with whom I once rode a Ferris wheel to the stars from which I have never ever come down

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

After

Acknowledgments

About the Author

PROLOGUE

The first poster was put up within a day of the disappearance. In the end there’d be over 1,500 of them, plastering what seemed like every available inch of the village. All of them mass-produced by the owner of a local printing company who barely knew the scared-out-of-their-minds parents but figured it was the least he could do.

It was nail-gunned to a telephone pole in front of Fredo’s Famous Pizzeria, an example of doubly false advertising, since its pizza wasn’t famous or even well-known, and the pizzeria wasn’t owned by anyone named Fredo. The owner was a Serbian named Milche, who thought an Italian name made more fiscal sense. Being an aficionado of The Godfather, he’d picked Fredo over Michael, which seemed to him too Anglicized. Like many pizza parlors throughout Long Island, it had evolved into a hangout for the too-young-to-drink crowd, and when Milche would shoo the local adolescents out of the store at closing time, the reigning fourteen-year-old wiseass would turn and utter this famous if misquoted line: “You broke my heart, Fredo, you broke my heart.”

What was really breaking hearts was the subject of the poster placed on the telephone pole outside Fredo’s on July 10, 2007. MISSING it said in black letters printed in Helvetica bold, and underneath, a picture of six-year-old Jennifer Kristal. It was her first-grade school photo, a little girl all dolled up and smiling for the camera.

It was a dichotomy that was particularly hard to comprehend for any parent strolling by—what was innocence doing plastered to a telephone pole? Telephone poles were for garage sale notices, local politicians’ campaign posters, and handyman ads with phone number slips hanging down like stripper tassels. They weren’t for a six-year-old girl with a traffic-stopping smile who’d walked down the block to her best friend’s house one day—yes, she was just six, but it was only two houses away and it was summer, and it wasn’t like they lived in the projects or something. This was upper-class suburbia, for God’s sake, and her mom, Laurie, had walked her to their screen door and even stood and watched a bit while Jenny skipped down the front steps—whereupon Jenny disappeared. Never showed up at her best friend Toni’s front door, never came home.

Poof.

That was hard for people to get their head around. A child just disappearing like that—like one of those sequined assistants in a magic act. It made existence seem too ephemeral, made them question their assumptions about everyday life. If little girls could just disappear into thin air, then what else was possible?

People didn’t know quite what to say to Laurie and Jake either—it was Jake who’d put up that first poster. People would generally avoid them if they had enough time to see them coming. Neighbors would duck into a store or pantomime that they must’ve left something in their car so that they had an excuse to turn around and go look for it. It was as if grief was catching. But, really, what do you say to parents whose kid had been stolen from them, whose only daughter had been taken God knows where—four states away by now, or in some dank basement, or the kind of place you didn’t even want to think about.

At first, there were some impressive and enthusiastic community efforts at pitching in. Not just from the owner of the local printing company, but from Laurie and Jake’s inner circle—the Kellys, whose daughter, Toni, was the best friend Jennifer had been on her way to see that afternoon, and the Shapiros, Kleins, and Mooneys, who were all fixtures at Laurie and Jake’s Fourth of July barbecues. The blowouts always featured a kick-ass fireworks show, courtesy of Jake’s stepbrother Brent, who drove up a truckload of cherry bombs and bottle rockets from North Carolina and, rumor had it, sold them on consignment to the neighborhood teens.

In fact, people who’d never even met the Kristals joined in the search, people from the neighborhood whose d

aughter or son was in the same first-grade class as Jennifer, or on the same soccer team. People who didn’t know Jennifer at all but had kids of similar age and experienced “there but for the grace of God” moments. And there were those who helped because they were simply drawn to that sort of thing.

There were Jennifer Park Searches, where volunteers groggily gathered at six A.M. in Hunter Park. They’d form a line straight across, not unlike the first wave of a football onside-kick formation, combing the tangled shrubs straight down to the lake. There was a Jennifer Hotline manned round the clock in those first few weeks, fueled by prodigious amounts of coffee provided gratis by the local Dunkin’ Donuts. A rotating support group set up shop in the Kristals’ house on Maple Street, bringing baked ziti, casseroles, bagels, and other assorted nourishment so that Laurie, Jake, and their son, Ben, could have something to eat. Not that Laurie or Jake consumed many calories that first week, but Ben, who was all of eight, walked around with a perpetual smear of doughnut glaze across his upper lip.

There was even a mass rally held at the local school auditorium, where the teary parents addressed the overflow crowd, beseeching anyone who’d seen anything, anything at all—a strange car, an odd-looking person—or overheard even a mildly suspicious comment to please, please report it to the Jennifer Hotline. The detective in charge of the investigation, Looper, a veteran of some twenty years, weighed in, providing the somewhat morose admonition that the first few days were crucial to there being a happy conclusion here—saying this even as the first few days were, in fact, coming to a close.

After Looper came to a dead end, there would be others placed in nominal authority: a private investigator hired by the Kristals named Lundowski who charged five hundred dollars a day to “beat the bushes”; Madame Laurette, a psychic, who claimed to have helped the police solve a number of baffling missing persons cases; and later on—much later—a cold case detective named Joe Pennebaker who would scrupulously go over every single piece of evidence again. Which sounds more impressive than it was, since there really wasn’t any evidence—not any physical evidence, anyway.

There were, of course, the usual false alarms—a registered sex offender who lived within running distance of the Kristals, a volunteered confession from an elderly man named Tom Doak, who kept a cache of pornography in his basement featuring young girls of indeterminate age. But the sex offender was found to have an airtight alibi, and Doak a long history of providing false confessions to the police—including copping to the assassinations of Medgar Evers, John Lennon, and, yes, even President Kennedy, though Doak would have been beginning second grade at the time.

After a while, that first poster, like the community’s interest in Jenny’s disappearance, slowly began to fade. As hard as that was to grasp for her grief-stricken parents, it happens that way. Life intrudes; there are family matters good, bad, and banal to contend with—graduations and divorces, anniversaries and funerals. A kind of communal attention deficit disorder seems to be on the uptick in this country anyway—the result of the internet, probably, where the next cigarette-smoking baby or celebrity train wreck is just seconds away. People lose interest at warp speed.

And there were other tragedies to wallow in for those who liked that sort of thing. For committed Republicans throughout the neighborhood—and Long Island was one of their last remaining downstate bastions—one of those tragedies was war hero John McCain losing the presidential election to a Chicago liberal who’d been a US senator for about ten seconds. A McCain/Palin poster was placed directly beneath Jenny’s, which despite almost a year and a half of inclement weather still retained her radiant smile, though her eyes had pretty much faded to two dull coins. Someone had crossed out MCCAIN/PALIN with blue spray paint and substituted HOPE AND CHANGE, BABY.

Hope was all but dead at the house on Maple Street, where Jake and Laurie remained. They’d refused to abandon the scene of the crime, because it was, after all, the scene of everything else involving Jennifer—her first birthdays, her first words, her first steps. And also because it happens to be what the parents of missing children do—stay put, because how else will their child ever find their way home?

By 2012, only half the poster remained, buried beneath ones for Mitt Romney and Chuck Schumer. Only the upper half, so you could still make out Jennifer Kristal’s eyes, which, like the Mona Lisa’s, seemed to be staring at you no matter which side of the street you were coming from. There were people who passed by and didn’t know whom the poster was for—people newly arrived in the neighborhood, and even some of the older residents, who’d simply forgotten that there’d ever been a missing child.

Her parents didn’t have that luxury. Five years from the date of Jenny’s disappearance, Jake made a new plea on a local Long Island TV station—like the messages NASA places on interstellar satellites rocketed into the void, doubtful anyone will read them, but willing to give it a shot: “Jenny, if you’re out there, I want you to know we will never stop looking for you. And if her kidnapper sees this, I want them to know that we just want her back. Please. That’s all we want. We won’t go to the police. We just want our daughter back.”

The local reporter followed with some depressing stats concerning the odds of Jennifer—or any missing child—still being alive after all that time. About on par with winning the New York Lottery (1 in 3,838,380, according to the New York State Bureau of Statistics). Yet, in an effort to provide some small sliver of hope, a few cases were cited—Elizabeth Smart, the girl found in Utah, for example, and a few other cases where a missing child was miraculously tracked down or simply walked into a police station one day and announced their identity. The same picture that had been nail-gunned to the telephone pole was prominently displayed on-screen, next to a police artist’s rendering of what Jennifer might look like now. A teenager who didn’t look very much like Jenny anymore, devoid of her neon smile and laughing eyes, as if the artist had tried to imbue it with whatever myriad horrors might have been perpetrated on her during all that time.

* * *

—

It was seven years later, when the original poster was only marginally visible, faded to almost complete white—the barest ghost image lurking there—when rain and snow and mud and time had mostly obliterated me, that I finally came home.

ONE

Forest Avenue, the neighborhood hub, three lanes on each side, with the Forest Avenue Diner—early-bird specials starting at five P.M., dessert and coffee included—standing watch on the northwest corner, or was it the northeast corner? Note to self: Check which way’s which. No matter, I remembered it.

I’d eaten in that diner, a Sunday tradition for the Kristal family, starting when I was small enough to fit into one of those red plastic baby chairs.

I wondered if they ate there now—Mom and Dad and Ben—maintaining the tradition against all odds, or if they’d long ago given it up, picked some other diner to eat their Sunday breakfasts in, or just stopped going out at all.

Just as I passed it, the door flew open. I could smell a mixture of pancakes, syrup, and fried eggs wafting through the door. Okay, I was hungry. But then I was always hungry—had been hungry as long as I could remember.

I had what felt like two dollars scrunched in my jeans pocket. Not enough for a muffin or even one egg. Coffee maybe . . . but what good would that do?

I floated on—floating is what it felt like, as if I were hovering over this little neighborhood, like you do in a dream, when you’re both in it and above it, everything half-remembered and half-not, things looking just the same and startlingly different. Just like me.

It was late fall, warm enough to think about ditching my zippered jacket. The brown leaves littering the sidewalk were so brittle they crunched into dust when I stepped on them.

I was making a game of it, in fact, not so much walking down the block as announcing my presence with each leaf-obliterating step. Hello, I’m back. Advancing in a ki

nd of zigzag pattern—some of the shopkeepers had swept the leaves into piles, forcing me to lunge here and there to keep it going, wondering if I looked high on something, like someone staggering home after an all-nighter.

That’s when I saw it—when I locked eyes with my former six-year-old self. Such barely there eyes—you really had to squint into the white void to see them. It was on a telephone pole outside a pizzeria. A dog was checking out the base of the pole, deciding whether or not it was going to grace it with its piss, the owner—a middle-aged woman—languidly scrolling through her phone and pretty much acting as if she wasn’t holding a leash with a dog attached to it.

I wanted to walk up to that pole and take a good look, but dogs scared me. So I waited until the lady finally stopped staring at her cell and moved on, yanking the dog away in mid-pee.

It was kind of like looking in a mirror, I thought, when I stepped up to the poster, except it was more like a magic mirror where you can look back in time—this parallel crazy world lurking just on the other side of it. I was coming back from that crazy world. And I was going to step back into my six-year-old room where all my toys were lined up just as I’d left them. Remember: The Bratz. Elmo. The two Barbies. A herd of plastic horses—one of them a Palomino I’d named Goldy.

Remember . . .

“Yoh.”

It took a second nasal yoh to understand that someone was actually speaking to me.

A guy. Nothing new about that. Put me on a sidewalk somewhere and odds are some dude will come chat me up. He might’ve been older than me but was somehow dressed younger, a red bandanna poking out of the back pocket of his low-slung jeans—which were precariously balanced on his hipbones and showing an inch or more of ugly brown boxers.

“You got a smoke?” he asked.

“No.”

He still hung around; maybe he was showing off for his friends, since there seemed to be an audience of boys—they looked like boys, too, younger than him—lurking by the pizzeria entrance.

Safe

Safe